Drug response with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a severe T-cell-mediated cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by rash, fever, involvement of internal organs, and systemic symptoms after prolonged use of certain drugs.

DRESS occurs in approximately 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 patients receiving medication, depending on the type of inducing drug. The majority of DRESS cases were caused by five drugs, in descending order of incidence: allopurinol, vancomycin, lamotrigine, carbamazepine, and trimethopridine-sulfamethoxazole. Although DRESS is relatively rare, it accounts for up to 23% of skin drug reactions in hospitalized patients.Prodromal symptoms of DRESS (drug response with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) include fever, general malaise, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, itching, burning of the skin, or a combination of the above. After this stage, patients often develop a measles-like rash that starts on the torso and face and gradually spreads, eventually covering more than 50% of the skin on the body. Facial edema is one of the characteristic features of DRESS and may aggravate or lead to new oblique ear lobe crease, which helps to distinguish DRESS from uncomplicated measles-like drug rash.

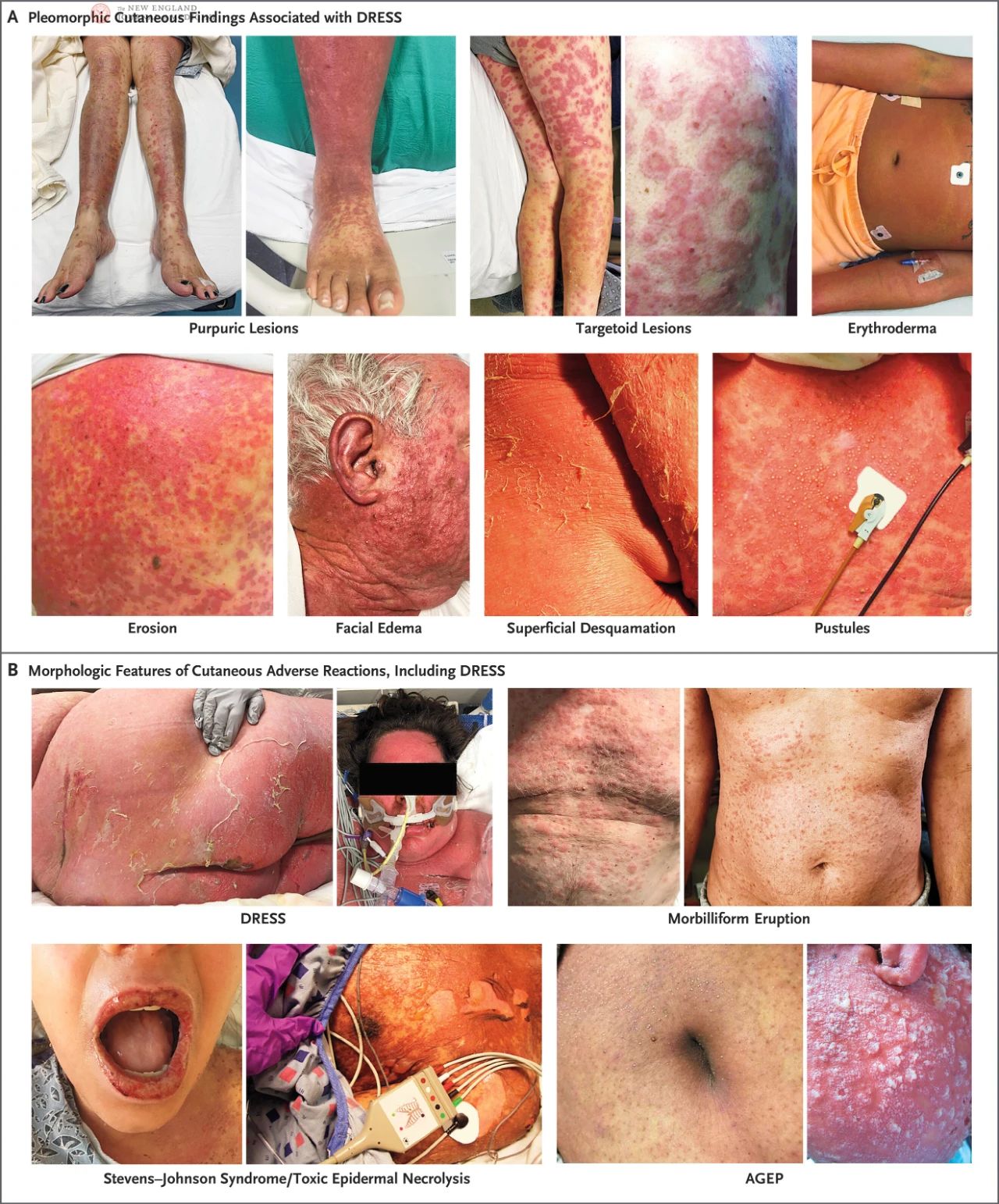

Patients with DRESS may present with a variety of lesions, including urticaria, eczema, lichenoid changes, exfoliative dermatitis, erythema, target-shaped lesions, purpura, blisters, pustules, or a combination of these. Multiple skin lesions may be present in the same patient at the same time or change as the disease progresses. In patients with darker skin, early erythema may not be noticeable, so it needs to be examined carefully under good lighting conditions. Pustules are common on the face, neck and chest area.

In a prospective, validated European Registry of Serious Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (RegiSCAR) study, 56% of DRESS patients developed mild mucosal inflammation and erosion, with 15% of patients having mucosal inflammation involving multiple sites, most commonly the oropharynx.In the RegiSCAR study, the majority of DRESS patients had systemic lymph node enlargement, and in some patients, lymph node enlargement even predates skin symptoms. The rash usually lasts more than two weeks and has a longer recovery period, when superficial desquamation is the main feature. In addition, although extremely rare, there are a small number of patients with DRESS who may not be accompanied by a rash or eosinophilia.

Systemic lesions of DRESS usually involve the blood, liver, kidneys, lungs, and heart systems, but almost every organ system (including the endocrine, gastrointestinal, neurological, ocular, and rheumatic systems) can be involved. In the RegiSCAR study, 36 percent of patients had at least one extra-cutaneous organ involved, and 56 percent had two or more organs involved. Atypical lymphocytosis is the most common and earliest hematological abnormality, whereas eosinophilia usually occurs in the later stages of the disease and may persist.

After the skin, the liver is the most commonly affected solid organ. Elevated liver enzyme levels may occur before the rash appears, usually to a milder degree, but may occasionally reach up to 10 times the upper limit of normal. The most common type of liver injury is cholestasis, followed by mixed cholestasis and hepatocellular injury. In rare cases, acute liver failure may be severe enough to require a liver transplant. In cases of DRESS with liver dysfunction, the most common pathogenic drug class is antibiotics. A systematic review analyzed 71 patients (67 adults and 4 children) with DRES-related renal sequelae. Although most patients have concurrent liver damage, 1 in 5 patients present with only isolated kidney involvement. Antibiotics were the most common drugs associated with kidney damage in DRESS patients, with vancomycin causing 13 percent of kidney damage, followed by allopurinol and anticonvulsants. Acute renal injury was characterized by increased serum creatinine level or decreased glomerular filtration rate, and some cases were accompanied by proteinuria, oliguria, hematuria or all three. In addition, there may be only isolated hematuria or proteinuria, or even no urine. 30% of affected patients (21/71) received renal replacement therapy, and while many patients regained kidney function, it was unclear whether there were long-term sequelae. Lung involvement, characterized by shortness of breath, dry cough, or both, was reported in 32% of DRESS patients. The most common pulmonary abnormalities in imaging examination included interstitial infiltration, acute respiratory distress syndrome and pleural effusion. Complications include acute interstitial pneumonia, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia, and pleurisy. Since pulmonary DRESS is often misdiagnosed as pneumonia, diagnosis requires a high degree of vigilance. Almost all cases with lung involvement are accompanied by other solid organ dysfunction. In another systematic review, up to 21% of DRESS patients had myocarditis. Myocarditis may be delayed for months after other symptoms of DRESS subside, or even persist. The types range from acute eosinophilic myocarditis (remission with short-term immunosuppressive treatment) to acute necrotizing eosinophilic myocarditis (mortality of more than 50% and median survival of only 3 to 4 days). Patients with myocarditis often present with dyspnea, chest pain, tachycardia, and hypotension, accompanied by elevated myocardial enzyme levels, electrocardiogram changes, and echocardiographic abnormalities (such as pericardial effusion, systolic dysfunction, ventricular septal hypertrophy, and biventricular failure). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging can reveal endometrial lesions, but a definitive diagnosis usually requires an endometrial biopsy. Lung and myocardial involvement is less common in DRESS, and minocycline is one of the most common inducing agents.

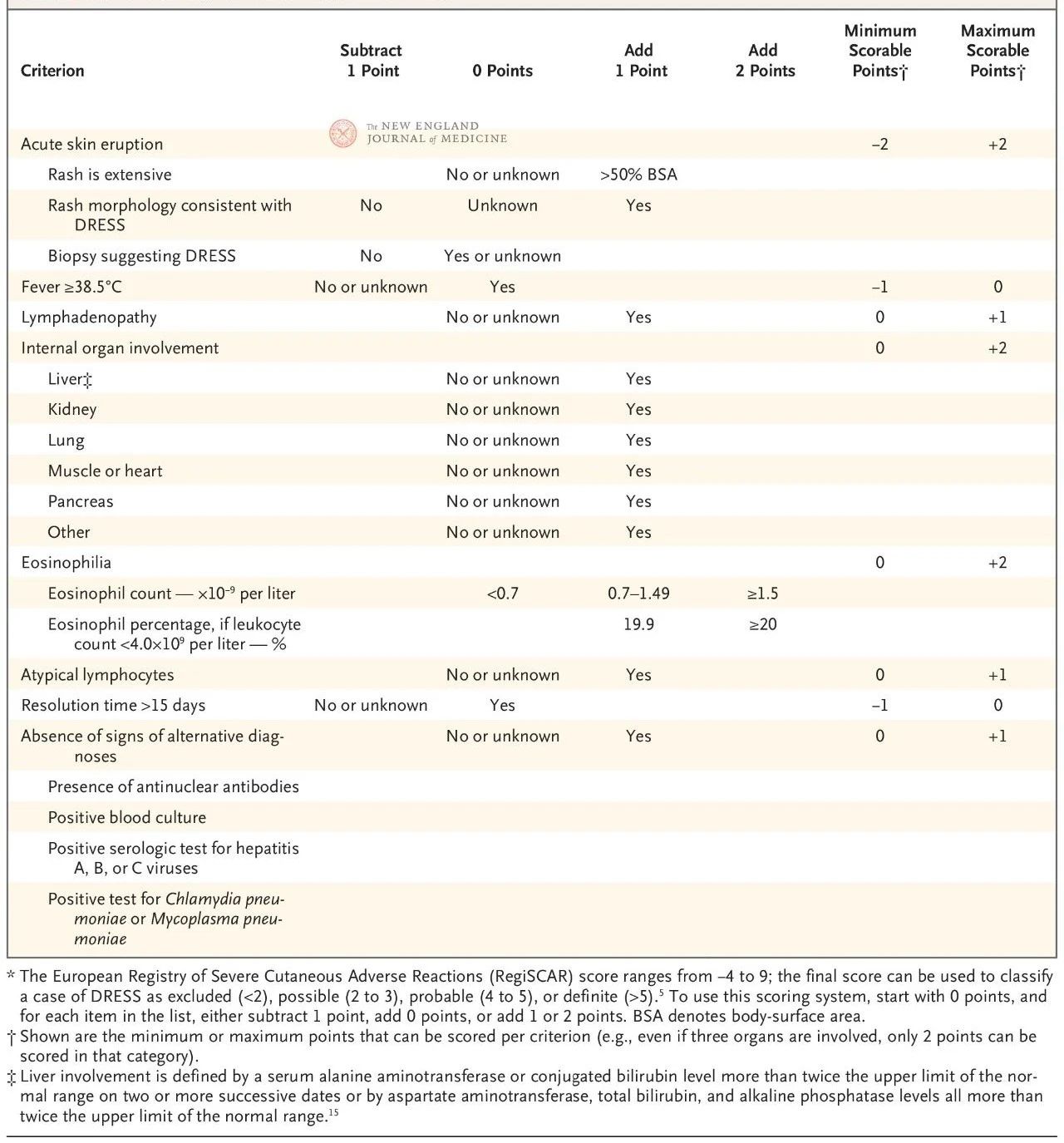

The European RegiSCAR scoring system has been validated and is widely used for the diagnosis of DRESS (Table 2). The scoring system is based on seven characteristics: core body temperature above 38.5°C; Enlarged lymph nodes in at least two locations; Eosinophilia; Atypical lymphocytosis; Rash (covering more than 50% of the body surface area, characteristic morphological manifestations, or histological findings consistent with drug hypersensitivity); Involvement of extra-cutaneous organs; And prolonged remission (more than 15 days).

The score ranges from −4 to 9, and diagnostic certainty can be divided into four levels: a score below 2 indicates no disease, 2 to 3 indicates probable disease, 4 to 5 indicates very likely disease, and more than 5 indicates a diagnosis of DRESS. The RegiSCAR score is particularly useful for retrospective validation of possible cases because patients may not have fully met all diagnostic criteria early in the disease or have not received a complete assessment associated with the score.

DRESS needs to be distinguished from other serious skin adverse reactions, including SJS and related disorders, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and acute generalized exfoliating impetigo (AGEP) (Figure 1B). The incubation period for DRESS is usually longer than for other serious skin adverse reactions. SJS and TEN develop quickly and usually resolve on their own within 3 to 4 weeks, while DRESS symptoms tend to be more persistent. Although mucosal involvement in DRESS patients may need to be distinguished from SJS or TEN, oral mucosal lesions in DRESS are usually mild and less bleeding. Marked skin edema characteristic of DRESS may lead to catatonic secondary blisters and erosion, while SJS and TEN are characterized by full-layer epidermal exfoliation with lateral tension, often showing Nikolsky’s sign positive. In contrast, AGEP usually appears hours to days after exposure to the drug and resolves rapidly within 1 to 2 weeks. The rash of AGEP is curved and composed of generalized pustules that are not confined to the hair follicles, which is somewhat different from the characteristics of DRESS.

A prospective study showed that 6.8% of DRESS patients had features of both SJS, TEN or AGEP, of which 2.5% were considered to have overlapping severe skin adverse reactions. The use of RegiSCAR validation criteria helps to accurately identify these conditions.

In addition, common measles-like drug rashes usually appear within 1 to 2 weeks after exposure to the drug (re-exposure is faster), but unlike DRESS, these rashes are not usually accompanied by elevated transaminase, increased eosinophilia, or prolonged recovery time from symptoms. DRESS also needs to be distinguished from other disease areas, including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, vascular immunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, and acute graft-versus-host disease.

Expert consensus or guidelines on DRESS treatment have not been developed; Existing treatment recommendations are based on observational data and expert opinion. Comparative studies to guide treatment are also lacking, so treatment approaches are not uniform.

Clear disease-causing drug treatment

The first and most critical step in DRESS is to identify and discontinue the most likely causative drug. Developing detailed medication charts for patients may help with this process. With drug charting, clinicians can systematically document all possible disease-causing drugs and analyze the temporal relationship between drug exposure and rash, eosinophilia, and organ involvement. Using this information, doctors can screen out the drug most likely to trigger DRESS and stop using that drug in time. In addition, clinicians can also refer to algorithms used to determine drug causality for other serious skin adverse reactions.

Medication – glucocorticoids

Systemic glucocorticoids are the primary means of inducing remission of DRESS and treating recurrence. Although the conventional starting dose is 0.5 to 1 mg/d/kg per day (measured in prednisone equivalent), there is a lack of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of corticosteroids for DRESS, as well as studies on different dosages and treatment regimens. The dose of glucocorticoids should not be arbitrarily reduced until clear clinical improvements are observed, such as reduction of rash, eosinophil penia, and restoration of organ function. To reduce the risk of recurrence, it is recommended to gradually reduce the dose of glucocorticoids over 6 to 12 weeks. If the standard dose does not work, then “shock” glucocorticoid therapy, 250 mg daily (or equivalent) for 3 days, may be considered, followed by a gradual reduction.

For patients with mild DRESS, highly effective topical corticosteroids may be an effective treatment option. For example, Uhara et al. reported that 10 DRESS patients recovered successfully without systemic glucocorticoids. However, because it is not clear which patients can safely avoid systemic treatment, widespread use of topical therapies is not recommended as an alternative.

Avoid glucocorticoid therapy and targeted therapy

For DRESS patients, especially those at high risk for complications (such as infections) from the use of high doses of corticosteroids, corticosteroid avoidance therapies may be considered. Although there have been reports that intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) may be effective in some cases, an open study has shown that the therapy has a high risk of adverse effects, especially thromboembolism, leading many patients to eventually switch to systemic glucocorticoid therapy. The potential efficacy of IVIG may be related to its antibody clearance effect, which helps to inhibit viral infection or reactivation of the virus. However, due to the large doses of IVIG, it may not be suitable for patients with congestive heart failure, kidney failure, or liver failure.

Other treatment options include mycophenolate, cyclosporin and cyclophosphamide. By inhibiting T cell activation, cyclosporine blocks gene transcription of cytokines such as interleukin-5, thereby reducing eosinophilic recruitment and drug-specific T cell activation. A study involving five patients treated with cyclosporine and 21 patients treated with systemic glucocorticoids showed that cyclosporine use was associated with lower rates of disease progression, improved clinical and laboratory measures, and shorter hospital stays. However, cyclosporine is not currently considered a first-line treatment for DRESS. Azathioprine and mycophenolate are mainly used for maintenance therapy rather than induction therapy.

Monoclonal antibodies have been used to treat DRESS. These include Mepolizumab, Ralizumab, and benazumab that block interleukin-5 and its receptor axis, Janus kinase inhibitors (such as tofacitinib), and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (such as rituximab). Among these therapies, anti-interleukin-5 drugs are considered to be the more accessible, effective and safe induction therapy. The mechanism of efficacy may be related to the early elevation of interleukin-5 levels in DRESS, which is usually induced by drug-specific T cells. Interleukin-5 is the main regulator of eosinophils and is responsible for their growth, differentiation, recruitment, activation and survival. Anti-interleukin-5 drugs are commonly used to treat patients who still have eosinophilia or organ dysfunction after the use of systemic glucocorticoids.

Duration of treatment

The treatment of DRESS needs to be highly personalized and dynamically adjusted according to disease progression and treatment response. Patients with DRESS typically require hospitalization, and about a quarter of these cases require intensive care management. During hospitalization, the patient’s symptoms are evaluated daily, a comprehensive physical examination is performed, and laboratory indicators are regularly monitored to assess organ involvement and changes in eosinophils.

After discharge, a weekly follow-up evaluation is still required to monitor changes in the condition and adjust the treatment plan in time. Relapse may occur spontaneously during glucocorticoid dose decline or after remission, and may present as a single symptom or local organ lesion, so patients need to be monitored long-term and comprehensively.

Post time: Dec-14-2024