On April 10, 2023, U.S. President Joe Biden signed a bill officially ending the COVID-19 “national emergency” in the United States. One month later, COVID-19 no longer constitutes a “public health Emergency of International concern.” In September 2022, Biden said the “COVID-19 pandemic is over,” and that month there were more than 10,000 COVID-19-related deaths in the United States. Of course, the United States is not alone in making such statements. Some European countries declared an end to the COVID-19 pandemic emergency in 2022, lifted restrictions, and managed COVID-19 like influenza. What lessons can we draw from such statements in history?

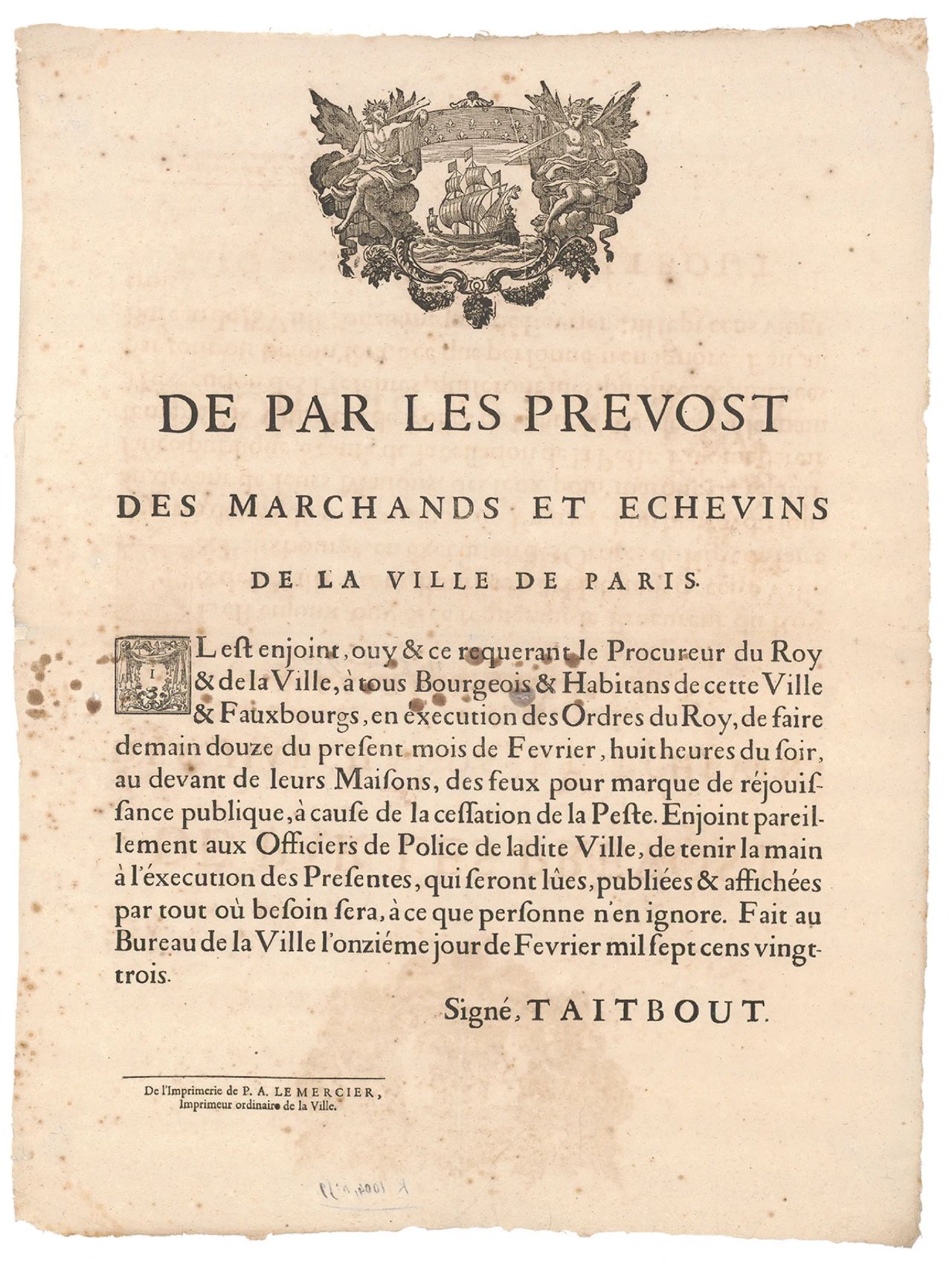

Three centuries ago, King Louis XV of France decreed that the plague epidemic raging in southern France was over (see photo). For centuries, plague has killed a staggering number of people around the world. From 1720 to 1722, more than half the population of Marseille died. The main purpose of the decree was to allow merchants to resume their business activities, and the government invited people to light bonfires in front of their homes to “publicly celebrate” the end of the plague. The decree was full of ceremony and symbolism, and set the standard for subsequent declarations and celebrations of the end of the outbreak. It also sheds a stark light on the economic rationale behind such announcements.

Proclamation declaring a bonfire in Paris to celebrate the end of the plague in Provence, 1723.

But did the decree really end the plague? Of course not. At the end of the 19th century, plague pandemics still occurred, during which Alexandre Yersin discovered the pathogen Yersinia pestis in Hong Kong in 1894. Although some scientists believe the plague disappeared in the 1940s, it is far from being a historical relic. It has been infecting humans in an endemic zoonotic form in rural areas of the western United States and is more common in Africa and Asia.

So we can’t help but ask: will the pandemic ever end? If so, when? The World Health Organization considers an outbreak to be over if no confirmed or suspected cases have been reported for twice as long as the maximum incubation period of the virus. Using this definition, Uganda declared the end of the country’s most recent Ebola outbreak on January 11, 2023. However, because a pandemic (a term derived from the Greek words pan [" all "] and demos [" people "]) is an epidemiological and sociopolitical event occurring on a global scale, the end of a pandemic, like its beginning, depends not only on epidemiological criteria, but also on social, political, economic, and ethical factors. Given the challenges faced in eliminating the pandemic virus (including structural health disparities, global tensions that affect international cooperation, population mobility, antiviral resistance, and ecological damage that can alter wildlife behavior), societies often choose a strategy with lower social, political, and economic costs. The strategy involves treating some deaths as inevitable for certain groups of people with poor socioeconomic conditions or underlying health problems.

Thus, the pandemic ends when society takes a pragmatic approach to the sociopolitical and economic costs of public health measures – in short, when society normalizes the associated mortality and morbidity rates. These processes also contribute to what is known as the “endemic” of the disease (” endemic “comes from the Greek en [" within"] and demos), a process that involves tolerating a certain number of infections. Endemic diseases usually cause occasional outbreaks of disease in the community, but do not lead to saturation of emergency departments.

The flu is an example. The 1918 H1N1 flu pandemic, often referred to as the “Spanish flu,” killed 50 to 100 million people worldwide, including an estimated 675,000 in the United States. But the H1N1 flu strain has not disappeared, but has continued to circulate in milder variants. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that an average of 35,000 people in the United States have died from the flu each year over the past decade. Society has not only “endemic” the disease (now a seasonal disease), but also normalizes its annual mortality and morbidity rates. Society also routinizes it, meaning that the number of deaths that society can tolerate or respond to has become a consensus and is built into social, cultural and health behaviours as well as expectations, costs and institutional infrastructure.

Another example is tuberculosis. While one of the health targets in the UN Sustainable Development Goals is to “eliminate TB” by 2030, it remains to be seen how this will be achieved if absolute poverty and severe inequality persist. TB is an endemic “silent killer” in many low – and middle-income countries, driven by a lack of essential medicines, inadequate medical resources, malnutrition and overcrowded housing conditions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the TB death rate increased for the first time in more than a decade.

Cholera has also become endemic. In 1851, the health effects of cholera and its disruption to International trade prompted representatives of the imperial powers to convene the first International Sanitary Conference in Paris to discuss how to control the disease. They produced the first global health regulations. But while the pathogen that causes cholera has been identified and relatively simple treatments (including rehydration and antibiotics) have been available, the health threat from cholera has never really ended. Worldwide, there are 1.3 to 4 million cholera cases and 21,000 to 143,000 related deaths each year. In 2017, the Global Task Force on Cholera Control set out a roadmap to eliminate cholera by 2030. However, cholera outbreaks have surged in recent years in conflict-prone or impoverished areas around the world.

HIV/AIDS is perhaps the most apt example of the recent epidemic. In 2013, at the Special Summit of the African Union, held in Abuja, Nigeria, member states committed to take steps towards the elimination of HIV and AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis by 2030. In 2019, the Department of Health and Human Services similarly announced an initiative to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States by 2030. There are about 35,000 new HIV infections in the United States each year, driven in large part by structural inequities in diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, while in 2022, there will be 630,000 HIV-related deaths worldwide.

While HIV/AIDS remains a global public health problem, it is no longer considered a public health crisis. Instead, the endemic and routine nature of HIV/AIDS and the success of antiretroviral therapy have transformed it into a chronic disease whose control has to compete for limited resources with other global health problems. The sense of crisis, priority and urgency associated with the first discovery of HIV in 1983 has diminished. This social and political process has normalized the deaths of thousands of people every year.

Declaring an end to a pandemic thus marks the point at which the value of a person’s life becomes an actuarial variable – in other words, governments decide that the social, economic, and political costs of saving a life outweigh the benefits. It is worth noting that endemic disease can be accompanied by economic opportunities. There are long-term market considerations and potential economic benefits to preventing, treating and managing diseases that were once global pandemics. For example, the global market for HIV drugs was worth about $30 billion in 2021 and is expected to exceed $45 billion by 2028. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, “long COVID,” now seen as an economic burden, could be the next economic growth point for the pharmaceutical industry.

These historical precedents make it clear that what determines the end of a pandemic is neither an epidemiological announcement nor any political announcement, but the normalisation of its mortality and morbidity through the routinisation and endemic of the disease, which in the case of the COVID-19 pandemic is known as “living with the virus”. What brought the pandemic to an end was also the government’s determination that the related public health crisis no longer posed a threat to society’s economic productivity or the global economy. Ending the COVID-19 emergency is therefore a complex process of determining powerful political, economic, ethical, and cultural forces, and is neither the result of an accurate assessment of epidemiological realities nor merely a symbolic gesture.

Post time: Oct-21-2023